Elaine van Dalen: Medical Perspectives on Epidemics in the Classical Islamic World

Faculty Profile

Elaine van Dalen is assistant professor of Classical Islamic Studies in the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies at Columbia University. She is a philologist working on medical, botanical, and agricultural texts from the Classical Islamic world. Her research questions relate to the history of medicine and philology, the transmission and translation of knowledge, and practices of medical commentary. She teaches Columbia’s Contemporary Civilization course, and MESAAS’ core course Asian Humanities.

Her most recent publication “Pediatrics in Medieval Islamic Theoria” (JAOS) analyzes the pediatric material in the Arabic commentaries (written tenth–fifteenth centuries) on the Hippocratic Aphorisms by exploring the traces of its late-antique origins and highlighting the influences of contemporary Islamic sources.

Medical Perspectives on Epidemics in the Classical Islamic World

In the case of an epidemic, stay at home, and clean your house daily, recommends the classical Islamic physician al Rāzī (d.c. 925). Epidemics afflicted the pre-modern Islamic world at regular intervals, and physicians, just as historians and other scholars, engaged with them throughout Islamic history. Classical Islamic physicians theorized about the nature of epidemics and their causes, and attempted to explain why so many people could be afflicted by a disease in a certain place at the same time. They also thought about the prevention of epidemics, and suggested cures. This information can be found in their medical compendia and treatises. After the Black Death in 1348, a new genre of plague treatises developed that specifically focused on the discussion of plagues, including new types of explanation and treatment.

The topic of contagion was contended in the Islamic world. Some ḥadīth clearly seem to subscribe the idea, such as “a sick person should not be brought to the healthy.” However, in the ḥadīth, “there is no contagion (ʿadwā), no augury, no owl, and no snake,” it seems the Prophet denies the possibility of interpersonal disease transmission. This led to many different opinions, especially among theologians, which are discussed for instance by the scholar Ibn Qutayba (d.889). The debate continued in post-classical times, too. Scholars such as Ibn al-Wardī (d. 1349) and al-Manbijī (d.1383), who wrote plague treatises after the Black Death, rejected the possibility of contagion based on this ḥadīth, while others such as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d.1350), Ibn Khātima (d.1369) and Ibn al-Khatīb (d.1374) considered contagion to be possible.

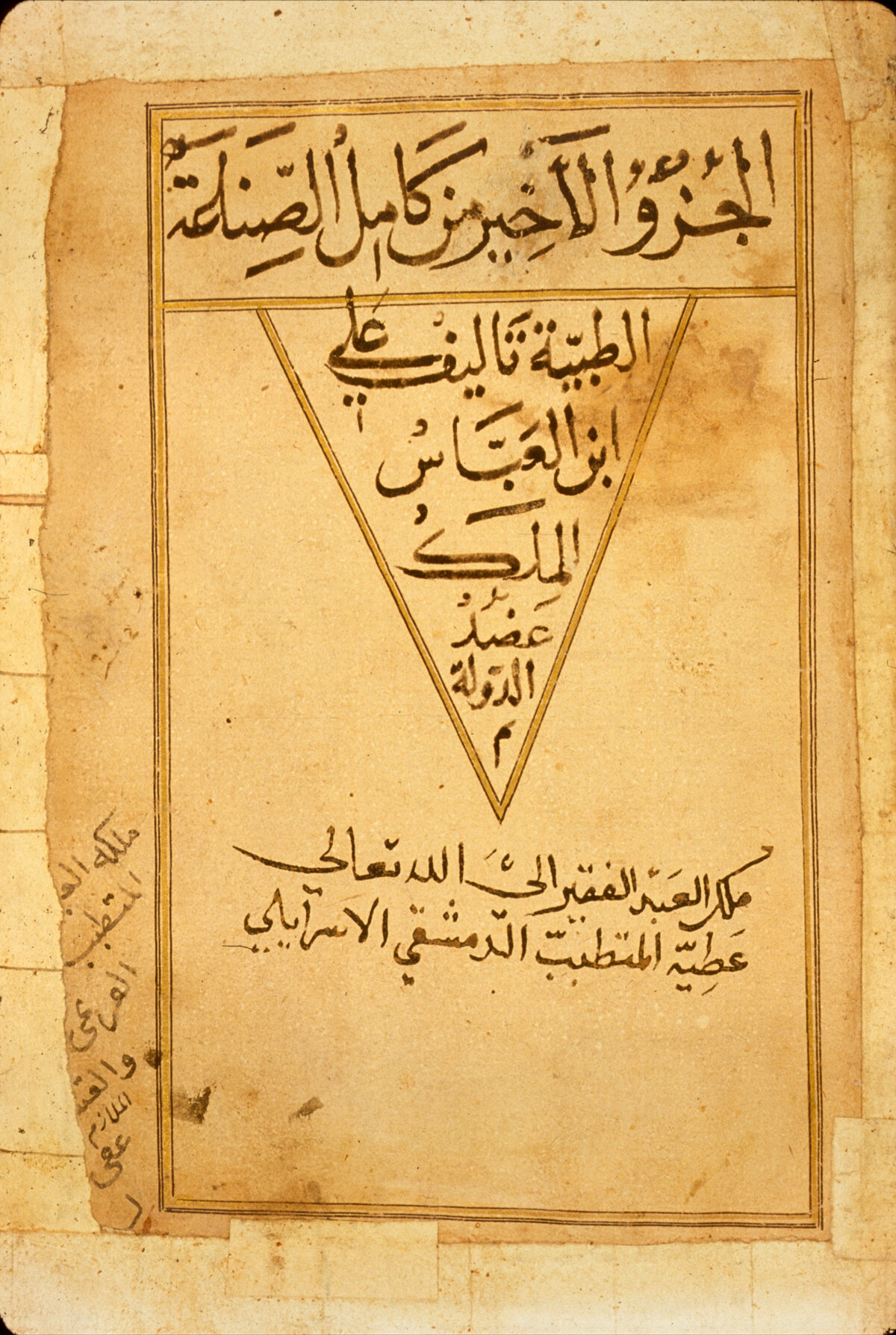

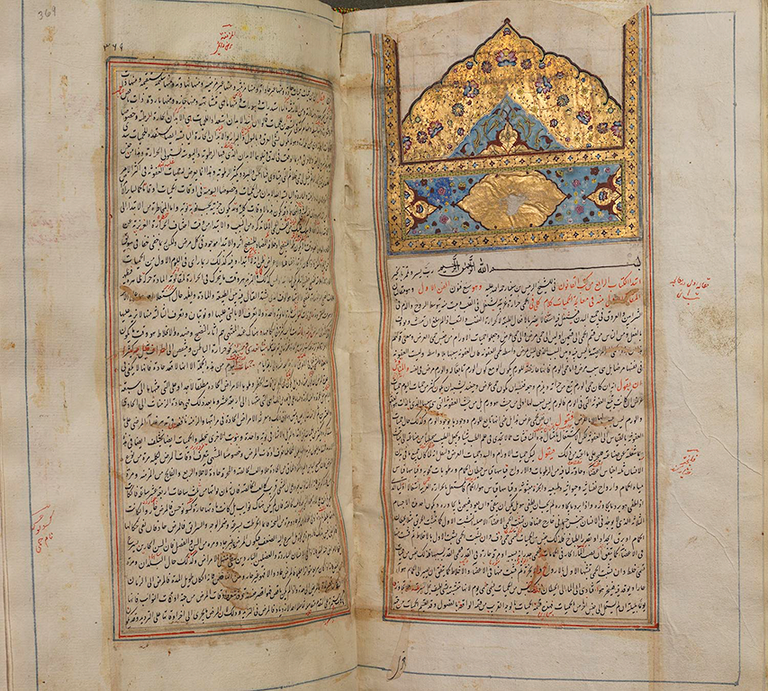

Among classical Islamic physicians, the topic of contagion wasn’t controversial. By the time these physicians began to compose their medical treatises, in the 9th century, the Justinian plague had been gone for over a 100 years. Small outbreaks of plague seem to have occurred in the 10th century, but these were isolated. As a result, plague, although mentioned and described, does not feature prominently in classical medical texts. However, epidemics and contagious diseases do. Physicians such as Thābit Ibn Qurra (d.901), Qusṭā Ben Lūqā (d.912), al-Ṭabarī (d.923), al-Rāzī (d.c. 925), and later al-Majūsī (d.c. 994), and Ibn Sīnā (d.1037) all upheld the possibility of disease transmission and knew about epidemic diseases. Yet they did not know about viruses or bacteria. Disease was perceived to be an imbalance in a body’s humoural balance, i.e. the combination of the amounts of phlegm, blood, black and yellow bile and their hot, cold, dry, and wet qualities, or an irregularity concerning the body’s vital heat or moisture. This raises the question of what these physicians thought contagion was, and, by extension, what epidemics were.

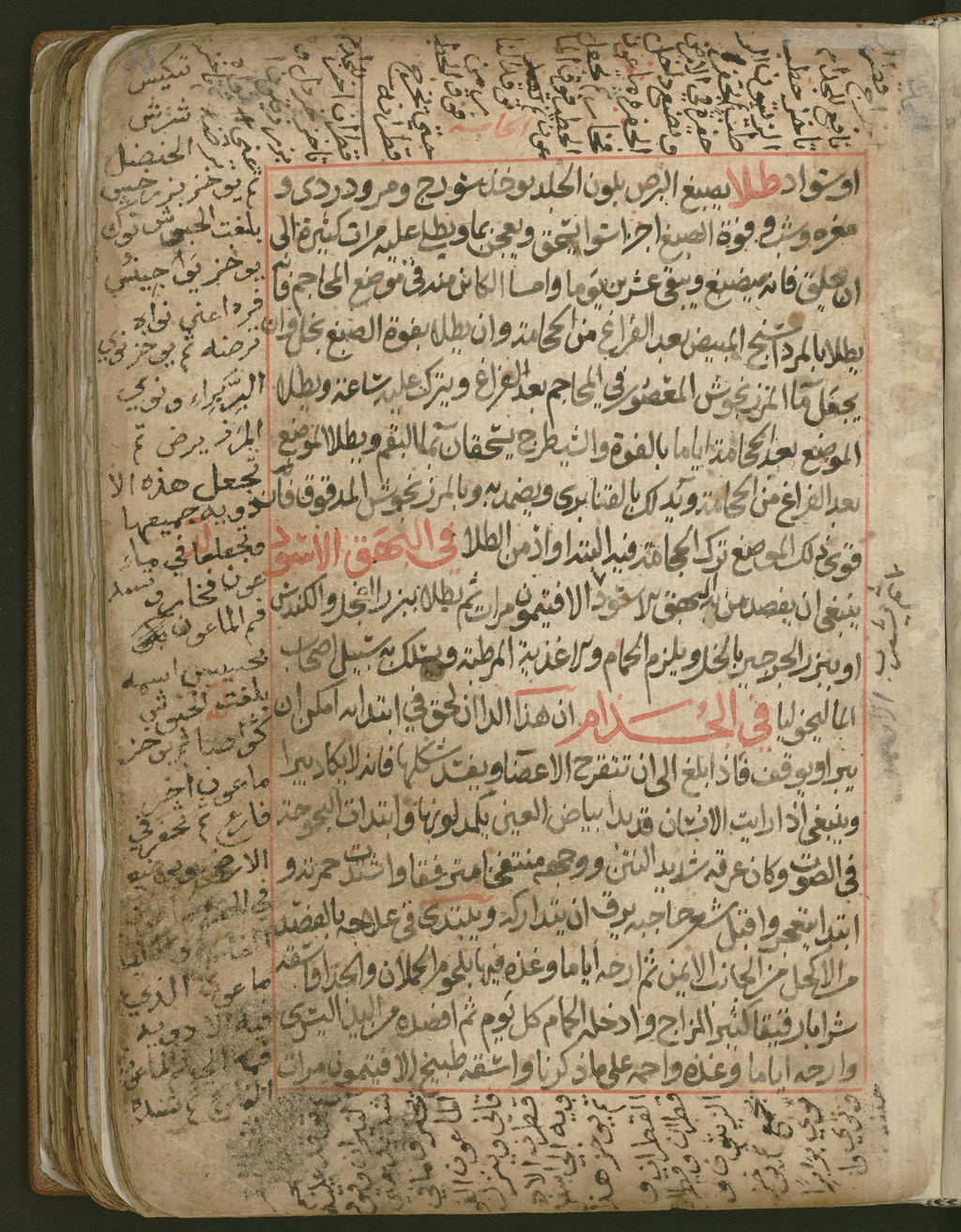

Classical Islamic physicians saw contagion (iʿdāʾ) as any form of disease transmission between individuals. It wasn’t a precisely defined concept, as it didn’t distinguish between infection or contagion. The physician al-Majūsī, moreover, includes inheritable diseases among transmittable diseases, too. Interpersonal transmission could take place when a sick person emanated bad vapours into the air, which upon inhaling could harm the humoural balance of a healthy person. But they also believed eye diseases, such as ophthalmia, could be transmitted through the emanation of rays, so that staring into a sick eye could make one’s own eye sick. Other diseases that were considered transmittable were smallpox, measles (first differentiated by al-Rāzī), scabies, leprosy, tuberculosis, and, according to some, plague and pestilential fevers. Some of these diseases could also be caused by pestilential air, for instance, according to Ibn Sīnā.

These diseases weren’t necessarily seen as epidemic diseases. The use of the terms for epidemic al-wāfida and wabāʾ changed over time, but in the classical period these terms were sometimes used as synonyms and sometimes seemed to have referred to slightly different concepts. On the one hand there was the idea of epidemic that comes close to the modern sense, that of a disease that happens to a lot of people at the same time in the same place, which was called al-wāfida, “the visiting.” Such diseases could be caused by certain habits regarding diet, exercise, or the air, as Galen had explained before. For example, the Egyptian physician Ibn Riḍwān also includes commonly consumed putrid water and food in a region as explanation for the occurrence of wide-spread disease (al-wāfida).

In addition, there was the concept of wabāʾ, which the classical physicians used to refer to a specific pestilential condition in the air which caused particular diseases such as epidemic fevers and smallpox. Such a corruption of air (miasma) could be caused by a deviation from the normal character of the seasons, possibly under influence of the planets. For instance, the end of summer could be hotter during a given year than normally, and this would affect people’s humour balance and cause illness. The air could also be corrupted due to bad vapours being absorbed in the air, from putrid lakes, rotting corpses, or other substances. This theory of air corruption is different from the theory of interpersonal transmission. While contagion can happen through air by means of bad vapours exhaled by ill people, the main reason of the corruption of air in the case of wabāʾ is not the breath of ill people.

Although the air was common to everyone in a certain region, it did not affect everyone in the same way. While large amounts of people became ill during epidemics, many remained unaffected. To explain this, physicians provided the provision that only if a person’s temperament was receptive to a particular corruption you would get ill. This meant the way someone’s humours, qualities, innate heat and moisture were configured based on their age, gender, and other non-natural factors could be in correspondence, or not, with the mixture of the air. Especially young boys, warns al-Rāzī, are receptive to corrupt air, due to their nature.

Certain signs predicted the arrival of a period of corrupt air, according to Ibn Sīnā. He writes that before an epidemic, frogs would flee and rats and other subterranean animals would appear from the earth. Al-Rāzī describes the appearance of lightning in the sky before an epidemic. When an epidemic was about to happen, or already present, there were a number of preventive measures people could take to protect themselves. One way to stay safe was to make sure one’s temperament was not receptive to the epidemic by eating certain food products while avoiding others, sleeping enough and keeping up one’s spirits. It was also important to use incense to clean the air in one’s house from bad vapours and to wash one’s house daily with for instance water and vinegar. Al-Rāzī recommends staying away from ill people, or to meet them in places out of the wind.

In the case of an epidemic considered to be caused by a natural corruption in the air resulting from certain planetary movements, as per Ibn Sīnā, one can imagine that staying away from ill people only partly reduces the risk of becoming ill. One would need to stay away from the entire affected area, as per the ḥadīth, “if you hear of an outbreak of plague in a land, do not enter it,” or make sure the air in one’s house is kept clean. In historical sources, social-distancing measures can be seen in the case of a disease such as leprosy, which was considered transmittable, but not necessarily caused by wabāʾ. Examples of social distancing in the case of leprosy are already known from pre-Islamic Arabia. For instance, when the poet al-Ḥārith ibn Ḥilliza al-Yashkurī (5th century AD) became ill with leprosy, he still performed for the king of Ḥīra, ʿAmr ibn Hind, who to avoid contagion had screens put up between them. According to the historian al-Ṭabarī (d.923 AD, the ʿUmayyad caliph Walīd I (r 705-715) prevented leprosy patients from mingling with other people. He also gave them stipends and assigned servants to take care of them, so that they did not need to beg from healthy people.

After the Black Death of 1347, which afflicted the Islamic world just as it did Europe, scholars developed a new genre of plague treatises. While physicians in the classical period had known about plague, and described plague buboes in their treatises, plague did not occupy a central place. In the plague treatises this changed. What changed too, is that these works weren’t produced by physicians, but by jurists and hadith scholars. These were not only informed by contemporary medical theory, but also included ḥadīth material and prophetic medicine in their works. Examples are the works by Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī (d.1449), Ibn Khātima and Ibn al-Khaṭīb. While the latter two accepted the medical idea that plague was caused by miasma, Ibn Ḥajar believed that plague was caused by jinn. If it had a natural cause, he argued, it would also have had a natural cure, which scholars at the time did not know. Ibn Ḥajar (d.1449) recommended reading the throne verse from the Qurʾān (Q 2:255) in a house for three consecutive nights to prevent the plague from entering. Ibn al-Khātima, in contrast, stays closer to the medical advises of the time. He explains how one can guard oneself for the plague by managing the effects of the non-natural factors, including food and exercise, and mental state. To keep up one’s spirits, Ibn al-Khātima recommends reading nice books, such as the Qurʾān, satire, and history works. Reading good books and generally taking care of one’s mental health sound like excellent advice in the middle of this pandemic.

For further reading, I have added a bibliography of excellent scholarship on these topics.